Written by Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

| May 26, 2024

Reviewed by Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

A reinforcement schedule refers to the delivery of a reward (reinforcer) to strengthen a behavior (i.e., make it occur more frequently).

There are four types of reinforcement schedules: fixed ratio, variable ratio, fixed interval, and variable interval.

Each schedule rewards behavior after a set number of responses (ratio schedules) or after a certain interval of time has elapsed (interval schedules).

The different schedules lead to different patterns of behavior and each contain unique strengths and weaknesses.

The schedules of reinforcement were delineated by B. F. Skinner (1965) as part of operant conditioning and based upon Edward Thorndike’s Law of Effect (1898; 1905).

The Law of Effect states that,

Contents show“Responses that produce a satisfying effect in a particular situation become more likely to occur again in that situation, and responses that produce a discomforting effect become less likely to occur again in that situation” (Gray, 2007, p. 106).

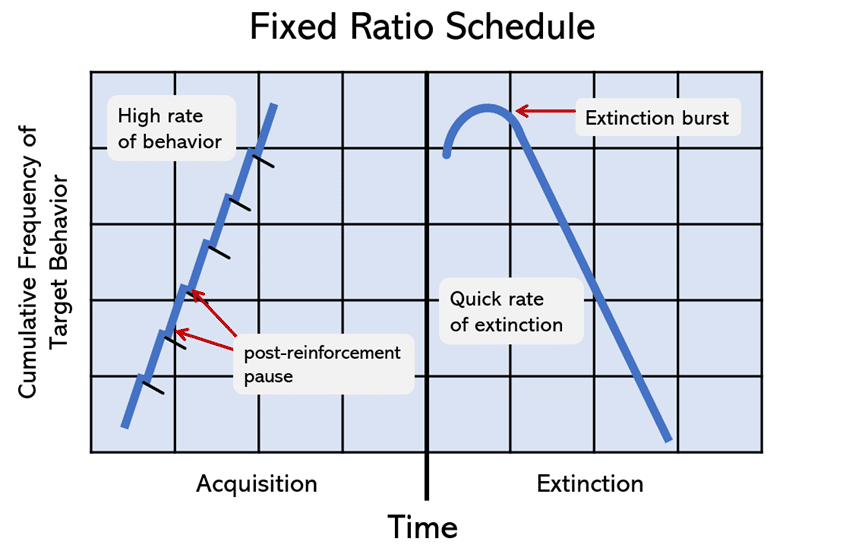

The fixed ratio schedule of reinforcement delivers a reward after a specific number of the target behavior have occurred.

For example, an FR-10 schedule means that a reward will be delivered after the target behavior has been exhibited 10 responses. The amount of time that elapses is irrelevant.

The FR schedule leads to the quick acquisition of behavior. That is, the organism (person or animal) in the schedule begins to exhibit the behavior rapidly.

The rate of respondent conditioning is frequent during the acquisition phase. However, if the reinforcer stops, the behavior will cease quickly as well. This is called extinction.

Shortly after reinforcement has been terminated, the animal (or person) may exhibit an extinction burst. That is a sudden increase in the target behavior.

The other notable pattern in this schedule is the post-reinforcement pause. The frequency of behavior will take a slight dip after each reinforcer.

| Fixed Ratio Pros | Fixed Ratio Cons |

| 1. High response rates | 1. Post-reinforcement pause |

| 2. Easy to implement and understand | 2. May lead to burnout or fatigue |

| 3. Predictable reinforcement pattern | 3. Less resistant to extinction |

Fixed Ratio Schedule Example

Video Game Play: Every time the player captures 20 monsters, they are rewarded with special powers

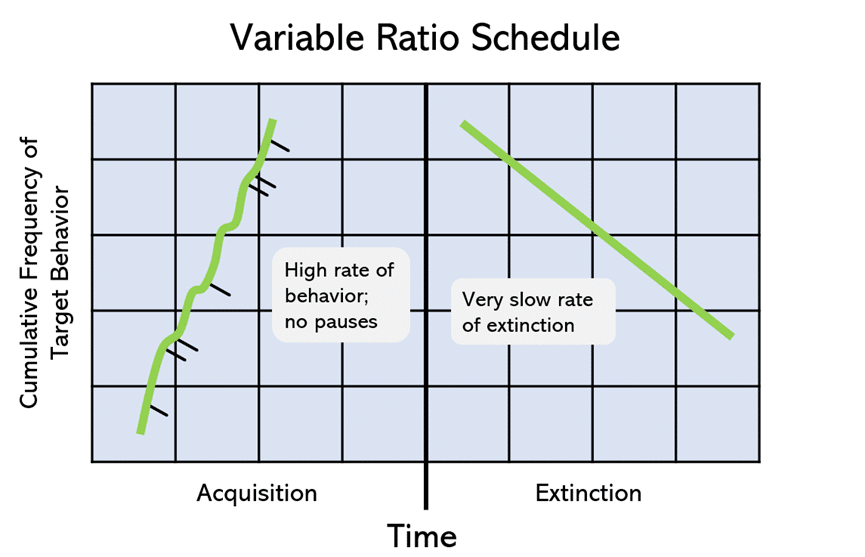

The variable ratio schedule delivers the reinforcer after the target behavior is exhibited, but the number of occurrences required changes.

Sometimes the reinforcer will be delivered after the behavior has been exhibited a few times, and sometimes it may take a large number of occurrences.

For example, a VR-10 schedule means that, on average, the behavior must be exhibited 10 times in order for the reward to occur. The behavior might be rewarded after 3 occurrences, then 2, then 7, and so on. Although the number changes, the average over a period of time will be 10.

The variable ratio schedule can produce quick acquisition if the ratio of behavior to reward is high. The organism picks-up on the contingency of behavior to reinforcer quickly.

Once the reward has been terminated, extinction will be slow. It takes a while for the organism to figure out that behavior is no longer rewarded.

| Variable Ratio Pros | Variable Ratio Cons |

| 1. High and consistent response rates | 1. More difficult to implement |

| 2. Resistant to extinction | 2. May lead to gambling-like behavior |

| 3. Encourages persistence in behavior | 3. May result in frustration or anxiety |

Variable Ratio Schedule Example

Slot Machines: The payoff of a slot machine is unpredictable. Who knows how many lever-pulls it will take before finally winning.

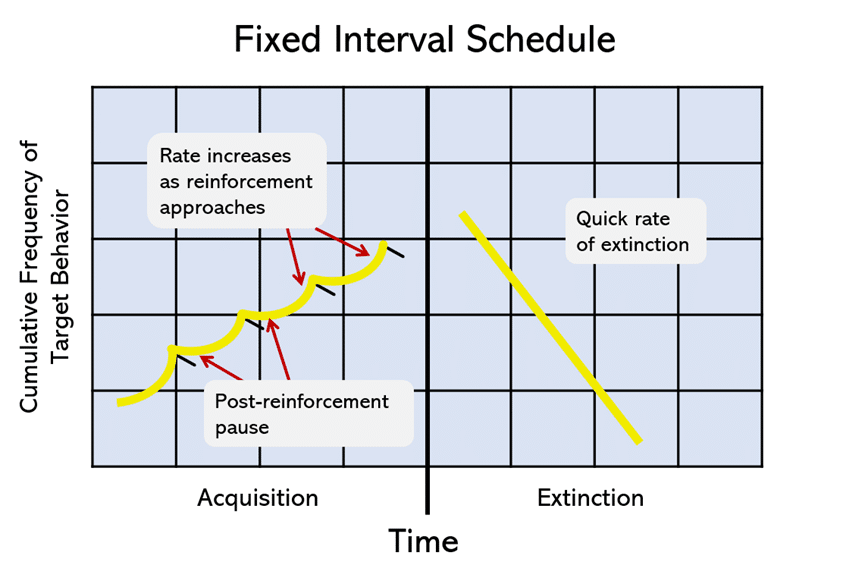

The fixed interval schedule of reinforcement rewards the first behavior that is exhibited after a specific period of time has elapsed.

The interval of time does not change and the number of target behaviors that occur during the interval is irrelevant. Among the four reinforcement schedules, the fixed interval produces the lowest frequency of the target behavior. Speed of acquisition and extinction depends on the length of the interval; the shorter the interval, the quicker the behavior will be exhibited and extinguished.

This schedule also produces a unique pattern of behavior called scalloping. Rate of behavior decreases immediately after reinforcement, and then shows a dramatic increase shortly before the next interval of time elapses.

| Fixed Interval Pros | Fixed Interval Cons |

| 1. Easy to implement and understand | 1. Lower response rates |

| 2. Predictable reinforcement pattern | 2. Scallop effect (increased response near reinforcement time) |

| 3. Suitable for long-term behavior change | 3. Less resistant to extinction |

Fixed Interval Schedule Example

Biweekly Paycheck: Most fast-food employees get paid every two weeks.

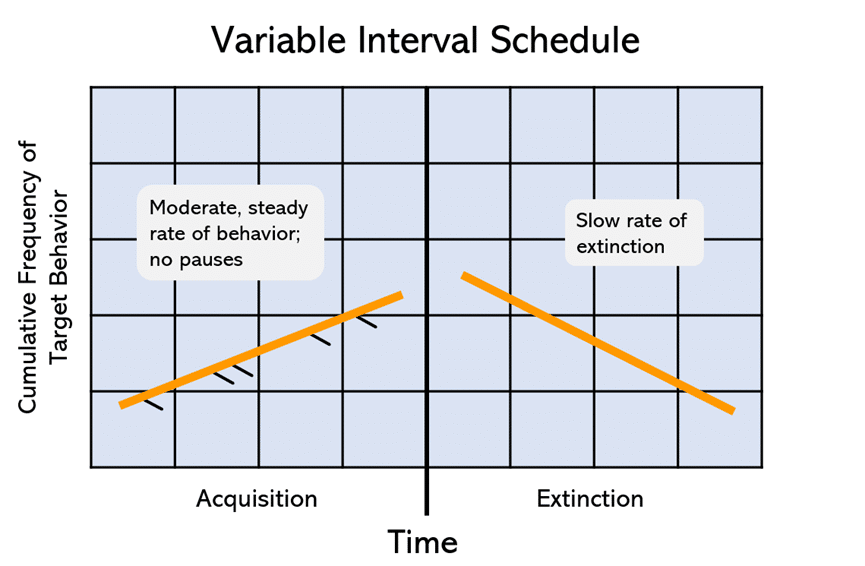

The variable interval schedule of reinforcement rewards the first behavior that is exhibited after a specific period of time has elapsed, but the length of time changes.

Sometimes the reinforcer will be delivered after a short duration, and sometimes the duration will be much longer.

For instance, with a VI-7 minutes schedule, the target behavior will be reinforced, on average, after 7 minutes has elapsed. However, the interval changes each time, so that on one occasion it might be 4 minutes, the next 3 minutes, but the third time it could be 12 minutes.

This schedule produces steady rate of behavior, slow acquisition and slow extinction.

| Variable Interval Pros | Variable Interval Cons |

| 1. Moderate and consistent response rates | 1. More difficult to implement |

| 2. Resistant to extinction | 2. Less precise control over behavior |

| 3. Encourages persistence in behavior | 3. May result in frustration or anxiety |

Variable Interval Schedule Example

Fishing: Sometimes a fish will bite as soon as the line is thrown, but sometimes 40 minutes might pass before getting a bite.

Probably the best example of the fixed ratio schedule of reinforcement is the video game. Although there is a lot of variation, one general principle is present in most: rewards come frequently.

For example, a lot of games involve the player striking specific icons. Each icon is associated with a reward value. The more icons the player hits, the more points awarded.

This is an FR-1 schedule, which means that the reinforcer is delivered after each instance of the target behavior.

As it turns out, research demonstrates that receiving all of those points is very rewarding; literally, there is a neurological basis for those feelings of reward.

Lorenz et al. (2015) summarized neuroimaging studies on video game players:

“…these studies show that neural processes that are associated with video gaming are likely to be related to alterations of the neural processing in the VS, the core area of reward processing” (p. 2).

This means that the reward centers in the player’s brain are activated when they receive points. Each token hit, stimulates the reward centers in the brain.

Of course, this increases playing behavior, thereby making the game more popular.

Research on treating individuals with behavioral or learning disabilities often involves a dense fixed interval schedule (Van Camp et al., 2000).

Using a dense schedule that rewards behavior frequently within short periods of time is effective at inducing quick acquisition. To decrease dependence on the reinforcer to maintain the desired target behavior, the schedule is gradually thinned.

However, variable time schedules may have greater ecological validity:

“because caregivers often are unable to implement FT schedules with a high degree of integrity in the natural environment” (p. 546).

Van Camp et al. (2000) examined the relative effectiveness of FT and VT schedules of reinforcement in treating two individuals with moderate to severe retardation. Both individuals displayed aggressive and sometimes self-injurious behavior.

“indicated that VT schedules were as effective as FT schedules in reducing problem behavior” (p. 552).

The implications of the VT schedule being effective are significant.

“Caregivers who implement treatment in the natural environment have numerous demands on their time and, thus, are likely to implement VT schedules even when they were taught to use FT schedules” (p. 556).

Keeping students focused on their classwork is a continuous challenge for all teachers, especially for teachers of young learners. Children are easily distracted and find it difficult to keep their attention on-task.

Riley et al. (2011) applied a fixed interval schedule of reinforcement to two students identified by a classroom teacher as having an especially hard time staying focused.

First, the children’s on-task and off-task behaviors were recorded during a baseline period. Next, the teacher was instructed to provide fixed-time (FT) delivery of teacher attention every 5 minutes.

The teacher offered praise for on-task behavior and redirected the student’s attention for off-task behavior.

The authors concluded that:

“This study demonstrates that FT attention delivery can be an effective strategy used to increase the on-task behaviors and decrease the off-task behaviors of typically-developing students” (p. 159).

Although it might be hard to believe, some of the world’s most feared predators are actually not very successful hunters. While at the same time, your neighbor’s cute cat can be quite deadly.

A predator’s success rate boils down to a particular reinforcement schedule, mainly the variable ration schedule.

For instance, if the success rate of a predator is 100%, that would be a fixed ratio schedule of one (FR-1); each hunt equals one meal. That doesn’t happen.

The actual success rate of most predators is in the single digits. That means that the number of attempts required in order to receive a reward changes.

One week, a predator might have to hunt 20 or 30 times before being successful. However, maybe the next week, they have success after just three attempts.

That’s a variable ratio schedule. The number of hunts required for reward is unpredictable.

The U. S. Congress works on a fixed interval work schedule. The begin in January and finish at the end of the year. Their target behavior is passing bills of legislation. If this is the case, then we should see a pattern of behavior that is typical of what is observed with the fixed interval schedule of reinforcement.

Critchfield et al. (2003) analyzed the annual congressional bill production over a period of 52 years, based on annual data from 1949 to 2000.

The data were taken from the ‘‘Resume´ of Congressional Activity,’’ a feature of the annual Daily Digest volume of the Congressional Record (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office).

“Across all years surveyed, few bills were enacted during the first several months of each session, and the cumulative total tended to accelerate positively as the end of the session approached. Across more than half a century, then, bills have been enacted in a distinct scalloped pattern in every session of each Congress” (p. 468).

There are four main reinforcement schedules. Some are based on how much time elapses, while others are based on the frequency of the target behavior. Each schedule produces a unique pattern of behavior.

Different schedules can be observed in various aspects of life. People that work in sales are sometimes rewarded at the end of each quarter (fixed interval), while others might receive a commission for each customer’s purchase (fixed ratio).

Slot machines are so addictive because they operate on a variable ratio schedule; one never knows when a reward with come.

Fixed- and variable-interval schedules can help children with learning disabilities. Rewarding their constructive behavior enhances their daily lives and can help them learn how to function in society.

Critchfield, T. S., Haley, R., Sabo, B., Colbert, J., & Macropoulis, G. (2003). A half century of scalloping in the work habits of the United States Congress. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36(4), 465-486.

Ferster, C. B., & Skinner, B. F. (1957). Schedules of reinforcement. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Gray, P. (2007). Psychology (6 th ed.). Worth Publishers, NY.

Lorenz, R., Gleich, T., Gallinat, J., & Kühn, S. (2015). Video game training and the reward system. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, article 40, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00040

Riley, J. L., McKevitt, B. C., Shriver, M. D., & Allen, K. D. (2011). Increasing on-task behavior using teacher attention delivered on a fixed-time schedule. Journal of Behavioral Education, 20(3), 149-162.

Skinner, B. F. (1965). Science and human behavior. New York: Free Press.

Staddon, J. E., & Cerutti, D. T. (2003). Operant conditioning. Annual review of psychology, 54(1), 115-144.

Watson, T. L., Skinner, C. H., Skinner, A. L., Cazzell, S., Aspiranti, K. B., Moore, T., & Coleman, M. (2016). Preventing disruptive behavior via classroom management: Validating the color wheel system in kindergarten classrooms. Behavior modification, 40(4), 518-540.

Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. The Psychological Review: Monograph Supplements, 2(4), i.

Thorndike, E. L. (1905). The elements of psychology. New York: A. G. Seiler.

Van Camp, C. M., Lerman, D. C., Kelley, M. E., Contrucci, S. A., & Vorndran, C. M. (2000). Variable‐time reinforcement schedules in the treatment of socially maintained problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33(4), 545-557.