- What is direct characterization?

- What is indirect characterization?

- What is the difference between direct and indirect characterization?

- The Bone Structure

- The Secret Snapshot

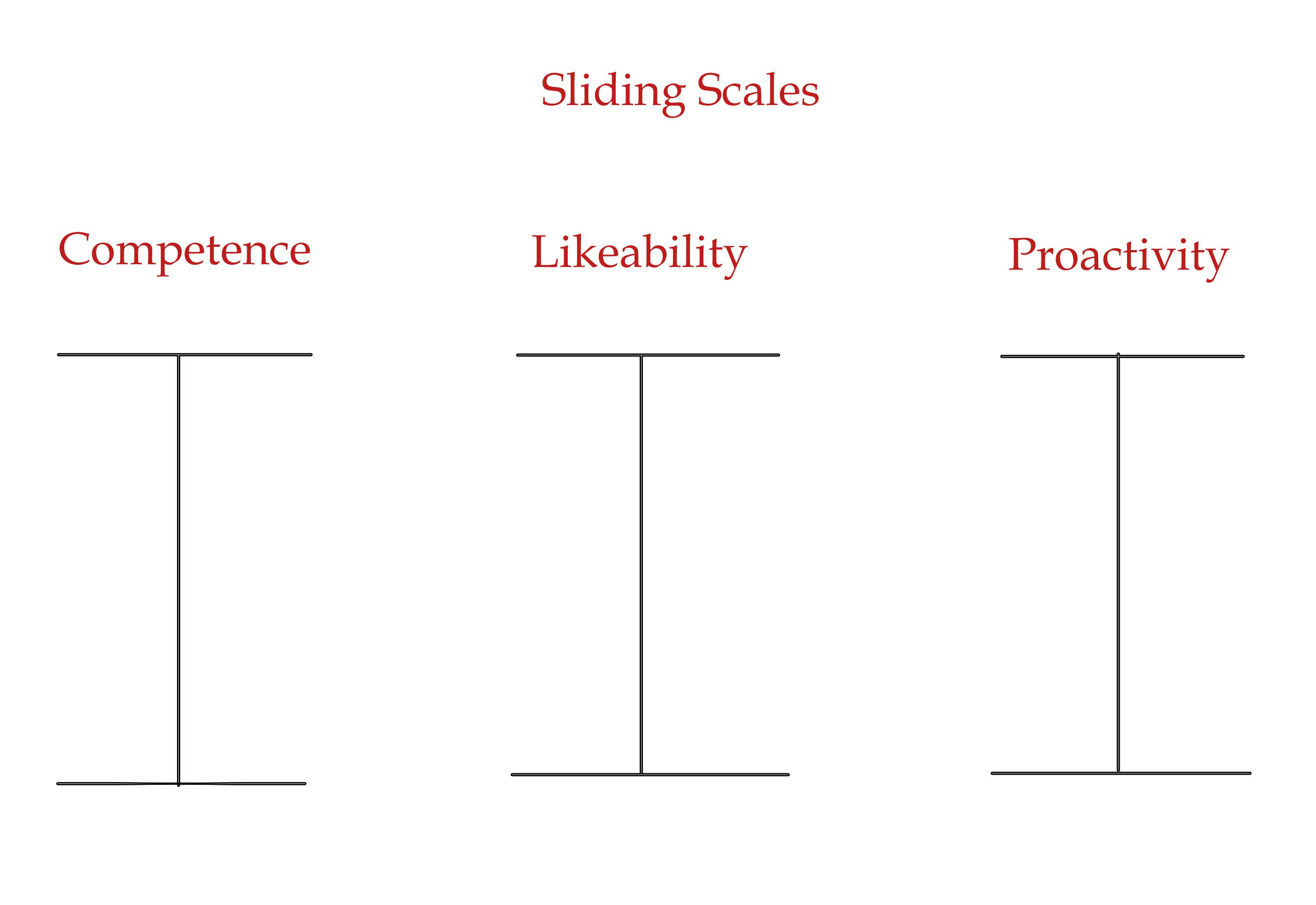

- Try Using Sliding Scales

What Is Characterization?

It’s always helpful to begin a new topic with a definition. While we’ve covered what characterization is in fiction, let’s take a look at a concrete definition courtesy of Dictionary.com.

These three definitions of the noun really do illuminate things further. The key elements for fiction writers lie in describing the individual quality of a person and giving a convincing representation of fictitious characters.

Similarly, the Cambridge dictionary defines it as the process of creating fictional characters in a book so that they seem real and natural.

The aim, therefore, is to create characters who feel alive and three-dimensional. That, in essence, is what characterization is all about.

What Are Indirect And Direct Characterization?

Now we’ve defined characterization on a broad level, let’s boil it down a little further.

It’s not an easy skill to come up with interesting and compelling characters. My research article exploring the reasons why people stopped reading a book revealed weak characterization to be one of the biggest culprits.

So what is characterization? It’s an umbrella term for the many facets that go into creating a fictional character. This covers everything from how they appear, how they think and feel, their background and upbringing… everything to do with who they are.

When it comes to writing fiction, there are two main types of characterization: direct and indirect characterization. Let’s look at each in turn before exploring the differences.

What is direct characterization?

This is also known as explicit characterization. As the name suggests, direct characterization is a no-frills approach to describing and revealing a character. It includes the likes of physical descriptions such as height, weight, peculiar features; hobbies and pursuits, such as a fondness for tennis; marital status, if relevant; or the likes of their job. Such forms of explicit characterization are crucial in revealing our characters and forming them in the minds of readers.

What is indirect characterization?

As you’d expect, indirect or implicit characterization is the opposite of direct characterization and encapsulates everything the narrative description doesn’t directly provide. So it covers the likes of:

- Dialogue

- Physical actions

- Thoughts

Indirect characterization is a terrific way of revealing more about a character without dumping a load of information on readers. Instead, subtle hints can be dropped into the narrative, encouraging readers to engage with the character to try and piece together the jigsaw of who they are.

What is the difference between direct and indirect characterization?

Both forms of characterization complement each other. It would be a dull read to be constantly fed direct descriptions. Readers enjoy the challenge of uncovering a character, of discovering who they really are.

Using indirect clues, like physical reactions and dialogue, is a terrific way of doing so. Not only does it encourage greater reader engagement, but it also avoids the risk of the writing and narrative becoming flat.

So that’s the biggest difference between direct and indirect characterization—the manner in which you wish to reveal the details of your character. Do you want the reader to know it all, or do you want to encourage them to work things out on their own?

So now we know a bit more about characterization, how do we go about coming up with characters? Let’s first consider what makes a character interesting.

Is Characterization Important?

As a writer, if you invest time on your direct and indirect characterization and fleshing out your character, you’re more likely to reap the rewards when readers finally get to read your book. You are, for instance, less likely to have a flat character leading the story, and your secondary characters are more likely to grab the attention and hearts of readers too.

So what makes a character likeable and interesting?

Many ingredients go into the broth of making an interesting character. Here are just a few examples:

- A character who experiences conflicted morals, such as those forced to choose between right or wrong, or the lesser of two evils.

- A character that can do something that no one else can. Only Frodo, with his untainted soul, can take the ring to Mordor. Only Daenerys Targaryen can withstand raging flames.

- A character that is out of their depth makes for an interesting read. So, for example, Prince Yarvi in Joe Abercrombie’s Half a King admits he is the least able person to be King, but try he must.

- Relationships with others. Is the character part of a gang of close friends, like in James Barclay’s The Chronicles of The Raven? Or is the character in love with someone who they cannot be with or long to be with, like Kvothe and Denna in Patrick Rothfuss’s The Name of the Wind?

- A character that reminds us of ourselves. This is a good way to create empathy. The character may do something that the reader has always wanted to do, but is unable. That’s the beauty of fiction—possibility.

- The character may be very proactive, something we’ll discuss below. This is one of the classic character archetypes of a likeable person.

- Another thing that makes for an interesting character is humour . When a character speaks in a certain way, or possesses a sharp wit, it can add to their entertainment value; naturally we want to spend time with them. As an example, the characters in The Chronicles of The Raven by James Barclay forever joke around with each other. Humour isn’t restricted to just dialogue too—incidents such as Laurel and Hardy-esque accidents make for good reading, as well as character’s reactions to things. Facial expressions, body language and the like can all help you avoid creating a flat character.

What Is An Example Of Characterization?

So we’ve looked in detail at what characterisation is. Now let’s take a look at an example.

In J.K. Rowling’s “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,” Severus Snape is a character rich with complexity and depth. Introduced as a sallow-skinned, hook-nosed, and greasy-haired professor, Snape immediately evokes suspicion and discomfort. His harsh demeanor and apparent favoritism towards Slytherin students further deepen the readers’ distrust. However, Rowling layers Snape’s character through his interactions and the revelations about his past.

Snape’s characterization unfolds through his actions and the perspectives of other characters. His relentless bullying of Harry contrasts sharply with moments where he inexplicably protects him, hinting at hidden motives.

Dumbledore’s trust in Snape adds another layer of complexity. Rowling gradually reveals Snape’s unrequited love for Lily Potter, Harry’s mother, which explains his actions and loyalty. This backstory transforms Snape from a mere antagonist to a tragic hero, showcasing his inner turmoil and the sacrifices he made out of love.

Rowling’s technique of peeling back the layers of Snape’s character through plot twists and revelations keeps readers engaged and allows for a deeper emotional connection. It’s a fantastic example of characterization in writing and how it can evolve and change over time.

When Should I Use Characterization In My Story?

A writer should characterize throughout the story to gradually build and reveal the depths of their characters.

Characterization is most effective when interwoven seamlessly into the plot, rather than delivered in large, expository chunks (AKA the info dump). Introduce key traits early on through actions, dialogue, and interactions with other characters. For instance, the way a character responds to conflict or their mannerisms can hint at their personality, such as being fearful or more of a fighter.

Significant moments of change, crisis, or conflict are prime opportunities for deeper characterization. These situations reveal how a character’s internal qualities influence their decisions and growth. For example, during a pivotal scene of betrayal or triumph, a character’s true nature is often exposed.

As we’ve seen in the example of Snape above, characterization should evolve as the story progresses. Continuous character development ensures characters remain dynamic and relatable, enhancing the reader’s investment in their journey.

Ultimately, effective characterization is a gradual, unfolding process that enriches the narrative and keeps readers engaged.

How Do I Characterize In My Story? A Look At The Best Tools

In this part of our guide on what characterization is, I’ve included some expert writing tips from bestselling writers, Brandon Sanderson in particular.

Sanderson’s tools for characterization are superb, allowing you to break down different key elements of who they are and what drives them.

The Bone Structure

By a long way, the best method of creating characters that I’ve come across is a simple device known as The Bone Structure. It was created by Lajos Egri (as far as I’m aware), a Hungarian playwright who set out his approach in his book, The Art Of Dramatic Writing (highly recommend).

Egri believed that if you can define three aspects of a person (or dimensions), you’d be able to create a fully-formed person. Three-dimensional in other words.

Those dimensions are:

- Physiology – the physical appearance

- Sociology – how society has influenced and shaped them

- Psychology – usually the product of physiology and psychology

To learn about each one, Egri prompts us to complete a questionnaire. The amount of detail you go into is up to you, but the more you’re able to define, the more fleshed out the character will be.

I’ve created a useful video that explains the approach and also guides you through the questionnaire. You can watch it below:

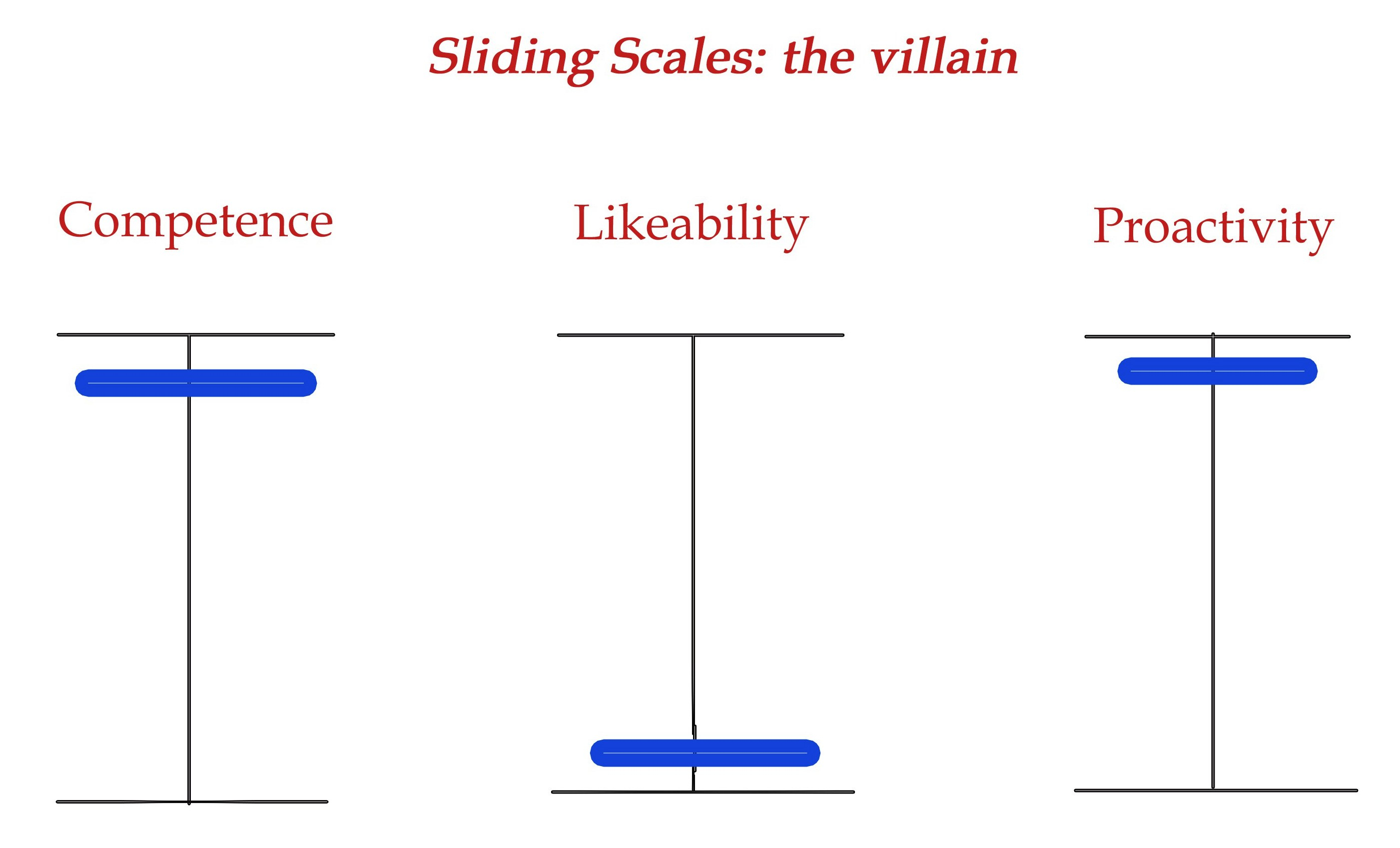

So that’s what the sliding scale looks like. Let’s see how it appears when we focus on a villain or antagonist.

Villains tend to be competent and proactive but fall low on the likeability scale. For example, Darth Vader is hell-bent on destroying the rebels and he’s not too shabby at it.

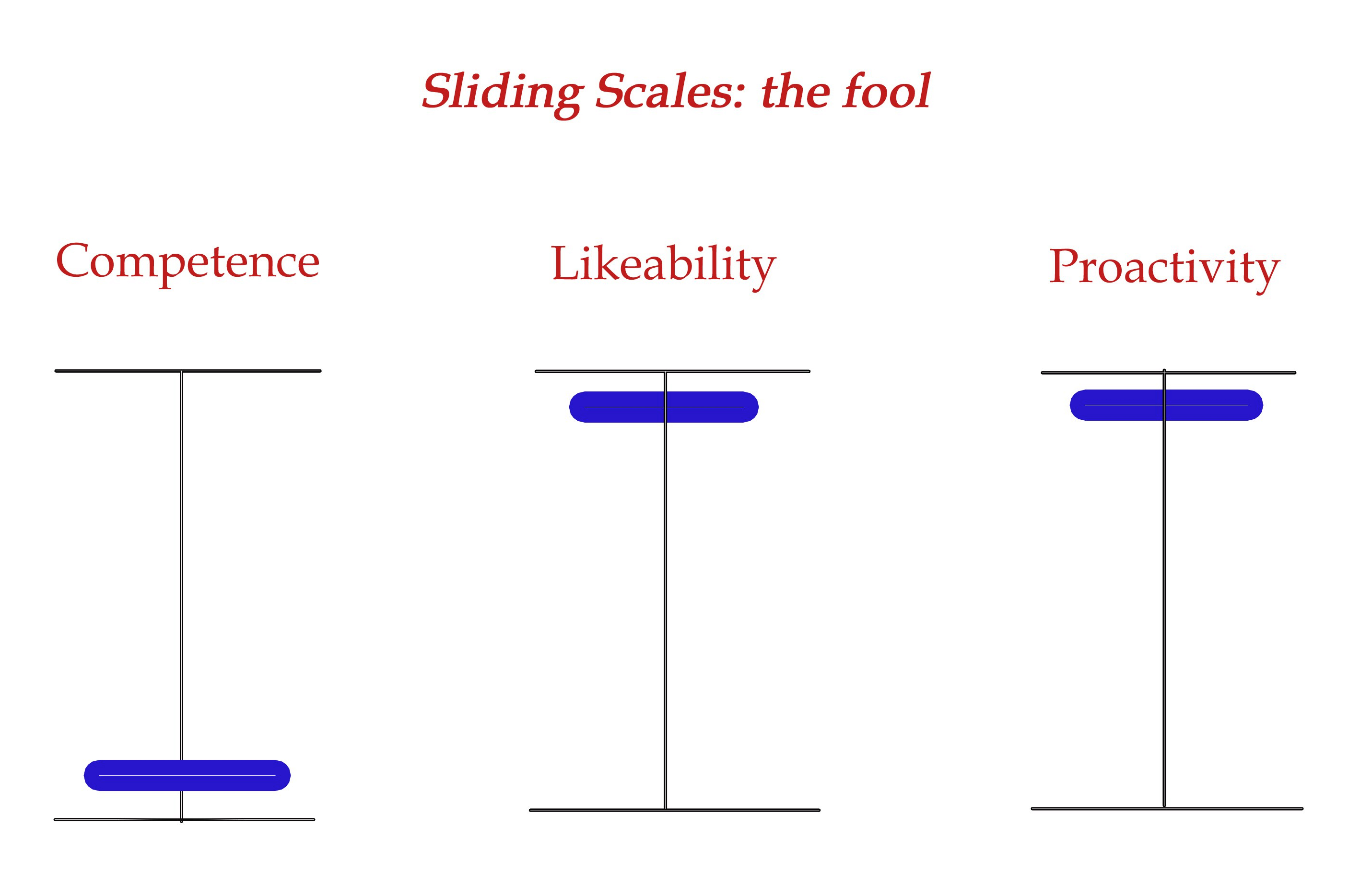

Let’s take a look at another example of characterization using sliding scales, this time with a “foolish” character. Everyone loves a trier, but as hard as they may try they never succeed or end up making things worse.

So now we’ve covered some examples, l et’s explore each scale in more detail .

Likeability

A good way to make a character likeable is to have other characters talk about them in positive ways. But strive for subtlety—what they say must have relevance to the tale.

It’s said if you want someone to like a character have them stroke a dog. If you want them to be hated, have them kick it, or worse, kill it.

Proactivity

We as readers naturally like fictional characters that move the story along, that try their best. Frodo, for example, was extremely motivated to take the ring to Mordor and didn’t stop until he got there. A reluctant character, someone riddled with fear, or who’s content with their lot, would fall low on the proactivity scale.

How can you make a character proactive?

- They may have dreams or aspirations.

- They may have an oath to keep, a promise to fulfil.

- A character may have been forced into a difficult situation, one they must get out of. For example, being enslaved or kidnapped.

- A character may have a longing to explore, to break free.

These are just a few; there are many more. See what you can come up with.

Competence

Most fictional characters tend to be competent in one way or another. There are the hapless village idiots, of course, that can’t do anything right (see ‘the fool’ scale above). Then you have characters who are competent in one particular area, like smithing or archery. And then we have our legendary heroes, like David Gemmell’s Druss the Legend, who can single-handedly defeat entire armies. But that’s not to say your average Joes can’t improve and develop some new skills. In fact, we love to see this happen. It’s a great way to grow a character (we’ll come to this shortly).

Highly competent characters tend to be likeable. We enjoy reading about a master or expert going about their business. Yes, it can get tedious, but done well it works. Over twenty movies down the line and people still aren’t bored of James Bond saving the world, massacring henchmen and blowing shit up.

Who doesn’t love watching Liam Neeson destroying half of Paris in Taken, Aragorn battling hordes of o rcs, or Pug from the Riftwar Saga destroying a planet? Highly competent characters don’t always have to be likeable, like Darth Vader, as shown in the villain scale above.

You don’t have to limit yourself to these three scales. You could go into more specific detail. If you’re a fan of computer games, you could approach it like picking your character’s attributes. I love games like The Elder Scrolls for how in-depth they go with characterization.

How Do You Create Characters With Disabilities And Imperfections?

A character may have imperfections. I explore character imperfections in some detail in my guide on how to plot a story. I’ll echo what was said there: not only do imperfections enable the reader to connect on an empathetic level with the character, it adds a whole other perspective to the struggles that they go through.

Imperfections also provide a source of conflict. A character could have physical imperfections, like Tyrion Lannister having dwarfism, or Yarvi in Joe Abercrombie’s Half a King having only one hand. Mental challenges could be involved too, like depression or a lack of confidence.

In my debut novel, Pariah’s Lament, one of my protagonists, Isy, is born with a birthmark that covers much of her face. This physical imperfection sees her scorned, bullied, abused and cast aside not just by society, but her own parents. I found introducing an imperfection like this was a terrific way of generating empathy toward Isy, such that readers instantly find her likeable.

Tips On Characterization From Leading Book Editors And Writers

I recommend dipping your nose into the book The First Five Pages by Noah Lukeman. Lukeman is one of the best literary agents in the game. He provides insights into the things to avoid as well as solutions and exercises. I’ll briefly go over a few things to avoid when it comes to crafting characters—for the solutions you’ll have to buy it!

- Don’t jump headfirst into the story without taking the time to establish the characters.

- Avoid cliché characters, like the Russian spy or the alcoholic policeman.

- Don’t introduce too many characters at once. The reader’s mind will boggle.

- Make it clear who the protagonist is.

- Make sure characters are relevant, even those on the periphery. If they’re not needed it uses up the reader’s energy.

- Be creative with character description. A unique description can enhance a story.

As well as this great advice from Lukeman, I’m also drawn to the advice handed down by Kurt Vonnegut. He said: “Every sentence must do one of two things—reveal character or advance the action.” Unless your narrative is a relentless series of explosions and high-speed chases, you’ll likely devote a significant portion of your story to character development.

The best sentences accomplish both revealing character and advancing the action, making your entire story a blend of action and characterization. In fiction, continuous characterization is crucial because readers crave connections with believable characters, regardless of the story’s setting. Constant characterization ensures your characters resonate with readers, making your story compelling and memorable.

If you’re itching for more on character creation, I’ve got a few more guides you can check out:

- A guide to characterisation from the Open University

If you need any more help with creating characters or characterization, then get in touch.

Richie Billing writes fantasy fiction, historical fiction and stories of a darker nature. He's had over a dozen short stories published in various magazines and journals, with one adapted for BBC radio. In 2021 his debut novel, Pariah's Lament, an epic fantasy, was published by Of Metal and Magic. Richie also runs The Fantasy Writers' Toolshed, a podcast devoted to helping writers improve their craft.

Most nights you can find him up into the wee hours scribbling away or watching the NBA.

Latest posts by richiebilling (see all)- Loaded Language: A Complete Definition With Examples - September 3, 2024

- How To Write A Premise For Your Story - August 29, 2024

- Brilliant Adjectives To Describe A Person - August 17, 2024